John Myhre

John Myhre has been nominated for five Academy Awards and has won two- one for his amazing work creating an entire Japanese village in Memoirs of a Geisha and another for the Best Picture winner Chicago. His enthusiasm for design has taken him across genres: he’s designed everything from musical blockbusters to period pieces to stylish action films and he’s not slowing down any time soon…

AS: What project are you currently working on?

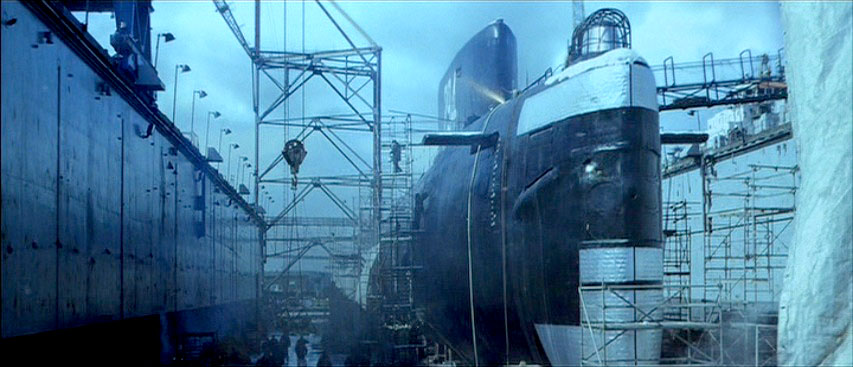

JM: I’m working on a really exciting project called Snow and the Seven which is a live-action version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs being made by Disney. That alone is really fun –I’m a huge Disney fan and just finished Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides for Disney and they were really wonderful to work with. But the really exciting thing about it is that it’s set in 19th century China. Snow is a colonial English girl. She has a step-mom who’s actually not bad at all but who gets possessed early on in the story by the spirit of an evil Chinese queen through an ancient Chinese mirror that they find. And Snow needs to flee away from her mother who’s out to get her. She flees through the wilds of China and runs into the Seven. But they’re not seven dwarfs, they’re seven warriors. Warriors from all around the world who are part of this organization and have been around for thousands of years. They keep the world safe from evil. Evil like evil queens. So Snow actually becomes one of the Seven and really becomes a warrior princess. It’s almost a superhero movie in a fun way and much more Pirates of the Caribbean than a kid’s traditional fairy tale story of Snow White.