Nathan Crowley 2.0

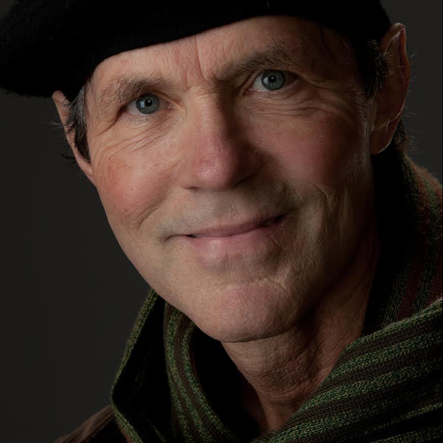

Nathan Crowley, award-winning production designer known for his partnership with director Christopher Nolan, has since branched out, working with new directors in large-scale fantasy and world-building. I interviewed him for a second time just after he finished what he called the best experience he’s had designing a film, the fantasy blockbuster Wicked with director Jon Chu…

For more about Nathan’s beginnings and the first part of his career, check out our first interview.

AS: Last we talked you said real scale in films is achieved in a physical location, like the stepwells in The Dark Knight. Now, designing a film like Wicked with a lot of scale but also with many more visual effects, how is your approach different?

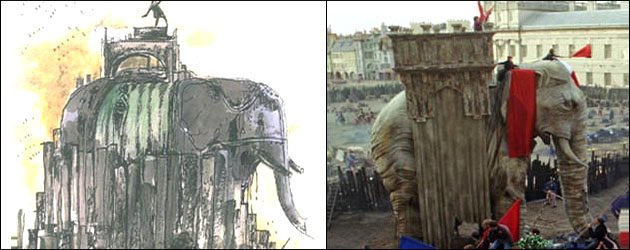

NC: My approach to filmmaking has always emphasized the power of location. You need that scale to get to the emotion of cinema. Of course with musicals you’re dealing with enormous crews and the director’s got three hundred dancers and they need to be looked after. You can’t take them to a remote location like Iceland, that doesn’t work! Traditionally, musicals rely on backlots to facilitate the musical numbers and Wicked, in particular, demanded fantastical sets and landscapes. And because it’s a fantasy musical, it becomes much more a weave of creation between large-scale practical set construction, real-world locations, and visual effects. We weave these together so the audience feels like there is something you can touch and there is a reality to it.

My challenge on Wicked was to try and leverage everything I knew from my previous films about practical filmmaking, practical set building, and get to some scale. This translated into constructing sets on a scale I had never attempted before, both in terms of size and height. This meant going up to fifty foot walls on backlots and installing massive water tanks.