Patrick Tatopoulos

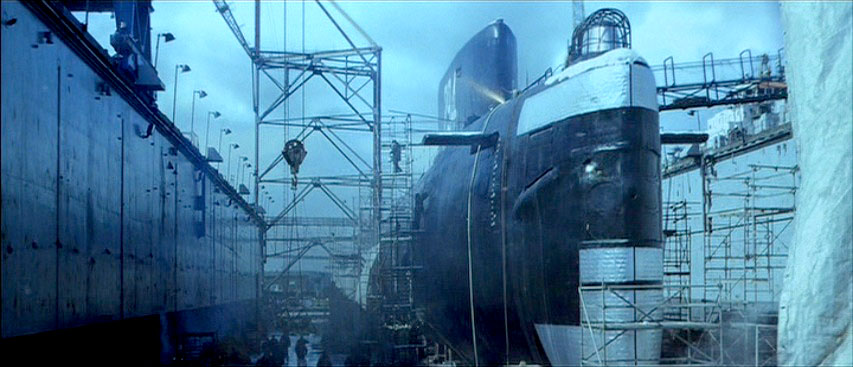

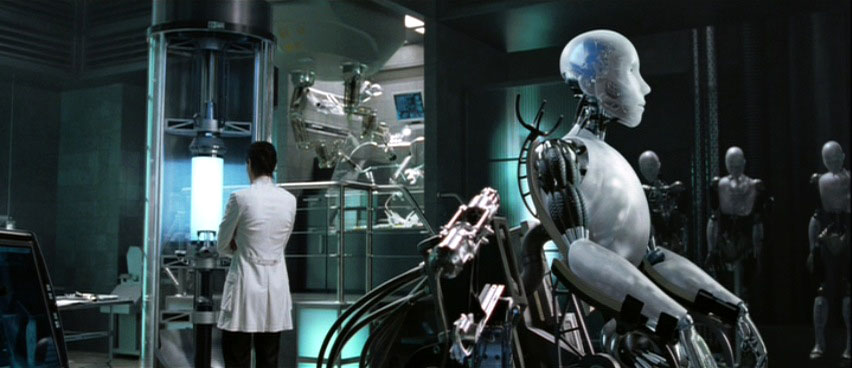

Patrick Tatopoulos production designed the blockbusters Independence Day, I, Robot, and Live Free or Die Hard. He is also famous for creating incredible creature effects for films such as Silent Hill, the Ruins, and the Underworld series, the last installment of which he directed. I ran into Patrick on the slopes at Big Bear and he agreed to share some of his wisdom.

NOTE: Following our original interview stick around for a 2020 addendum with Patrick’s updated take on the current state of our industry…

AS: You went from effects to production designer and now to director- how did you first start out?

PT: I left Europe and came to the States to be a sculptor or designer for creature effects. The thing that actually appealed to me the most about moviemaking was special makeup effects. That was my first big target. After seeing the movie the Thing I said, This is what I want to do. So in a few weeks I sculpted a bunch of creatures- I was in Greece at the time- then I took pictures and came to the States. I had a few meetings but the one that became really, really important was with a company called Makeup Effects Laboratories. Those guys ended up hiring me and getting me my Green Card so I could work as a creature sculptor. I spent a year or so sculpting, making molds, and designing creatures for them on a few small movies that came to the shop. I built a couple of creature effects for Star Trek: Next Generation and then a company came and we had to do Beastmaster 2. They saw my drawing and said, Hey Patrick we have a great production designer on board but he doesn’t draw. We would like someone like you to be the art director.